Indo-Iranian languages

| Indo-Iranian | |

|---|---|

| Indo-Iranic (Aryan) | |

| Geographic distribution | South, Central, West Asia and the Caucasus |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Indo-Iranian |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-5 | iir |

| Glottolog | indo1320 |

Distribution of the Indo-Iranian languages | |

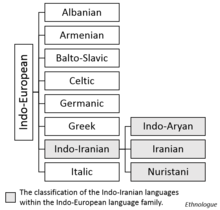

The Indo-Iranian languages (also known as Indo-Iranic languages[2][3] or collectively the Aryan languages[4]) constitute the largest and southeasternmost extant branch of the Indo-European language family. They include over 300 languages, spoken by around 1.5 billion speakers, predominantly in South Asia, West Asia and parts of Central Asia.

The areas with Indo-Iranian languages stretch from Europe (Romani) and the Caucasus (Ossetian, Tat and Talysh), down to Mesopotamia and eastern Anatolia (Kurdish languages, Gorani, Kurmanji Dialect continuum,[5] Zaza[6][7]) and Iran (Persian), eastward to Xinjiang (Sarikoli) and Assam (Assamese), and south to Sri Lanka (Sinhala) and the Maldives (Maldivian), with branches stretching as far out as Oceania and the Caribbean for Fiji Hindi and Caribbean Hindustani respectively. Furthermore, there are large diaspora communities of Indo-Iranian speakers in northwestern Europe (the United Kingdom), North America (United States, Canada), Australia, South Africa, and the Persian Gulf Region (United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia). The number of distinct languages listed in Ethnologue are 312,[8] while those recognised in Glottolog are 320.[9] The Indo-Iranian language with the largest number of native speakers is Hindustani language (Hindi-Urdu).[10]

Etymology

The term Indo-Iranian languages refers to the spectrum of Indo-European languages spoken in the Southern Asian region of Eurasia, spanning from the Indian subcontinent (where the Indic branch is spoken, also called Indo-Aryan) up to the Iranian Plateau (where the Iranic branch is spoken).

This branch is also known as Aryan languages, referring to the languages spoken by Aryan peoples, where the term Aryan is the ethnocultural self-designation of ancient Indo-Iranians. But in modern-day, Western scholars avoid the term Aryan since World War II, owing to the perceived negative connotation associated with Aryanism.

Origin

Historically, the Indo-Iranian speakers, both Iranians and Indo-Aryans, originally referred to themselves as the Aryans.[11][12] The Proto-Indo-Iranian-speakers generally associated with the Sintashta culture,[13][14][15] which is thought to represent an eastward migration of peoples from the Corded Ware culture.[16][17][18][19] The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials, and the culture is considered a strong candidate for the origin of the technology, which spread throughout the Old World and played an important role in ancient warfare.[20][21][22][23] There is almost a general consensus among scholars that the Andronovo culture, the successor of Sintasha culture, was an Indo-Iranian culture.[24][13] Currently, only two sub-cultures are considered as part of Andronovo culture: Alakul and Fëdorovo cultures.[25] The Andronovo culture is considered as an "Indo-Iranic dialect continuum", with a later split between Iranian and Indo-Aryan languages.[26] However, according to Hiebert, an expansion of the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) into Iran and the margin of the Indus Valley is "the best candidate for an archaeological correlate of the introduction of Indo-Iranian speakers to Iran and South Asia",[27] despite the absence of the characteristic timber graves of the steppe in the Near East,[28] or south of the region between Kopet Dag and Pamir-Karakorum.[29][b] Mallory acknowledges the difficulties of making a case for expansions from Andronovo to northern India, and that attempts to link the Indo-Aryans to such sites as the Beshkent and Vakhsh cultures "only gets the Indo-Iranian to Central Asia, but not as far as the seats of the Medes, Persians or Indo-Aryans". He has developed the Kulturkugel (lit. 'the culture bullet') model that has the Indo-Iranians taking over cultural traits of BMAC, but preserving their language and religion while moving into Iran and India.[31][27]

Sources

- Allentoft, Morten E.; et al. (11 June 2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. 522 (7555). Nature Research: 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507. S2CID 4399103.

- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- Anthony, D. W. (2009). "The Sintashta Genesis: The Roles of Climate Change, Warfare, and Long-Distance Trade". In Hanks, B.; Linduff, K. (eds.). Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals, and Mobility. Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–73. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511605376.005. ISBN 978-0-511-60537-6.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009), Empires of the Silk Road, Princeton University Press

- Blöcher, Jens; et al. (21 August 2023). "Descent, marriage, and residence practices of a 3,800-year-old pastoral community in Central Eurasia". PNAS. 120 (36): e2303574120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2303574120. PMC 10483636.

- Chernykh, Evgenii N. (2009). "Formation of the Eurasian Steppe Belt Cultures: Viewed through the Lens of Archaeometallurgy and Radiocarbon Dating". In Hanks, Bryan K.; Linduff, Katheryn M. (eds.). Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals, and Mobility. Cambridge University Press. pp. 115–145. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511605376.009. ISBN 978-0-511-60537-6.

- Chintalapati, Manjusha; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya (18 July 2022). "The spatiotemporal patterns of major human admixture events during the European Holocene". eLife. 11 (11): e77625. doi:10.7554/eLife.77625. PMC 9293011. PMID 35635751.

- Degtyareva, A. D.; Kuzminykh, S. V. (December 2022). "Metal tools of the Petrovka Culture of the Southern Trans-Urals and Middle Tobol: chemical and metallurgical characteristics". Сетевое издание. 4 (59). doi:10.20874/2071-0437-2022-59-4-3.

- Epimakhov, Andrey; Zazovskaya, Elya; Alaeva, Irina (7 August 2023). "Migrations and Cultural Evolution in the Light of Radiocarbon Dating of Bronze Age Sites in the Southern Urals". Radiocarbon: 1–15. doi:10.1017/RDC.2023.62.

- Grigoriev, Stanislav (1 April 2021). "Andronovo Problem: Studies of Cultural Genesis in the Eurasian Bronze Age". Open Archaeology. 7: 3–36. doi:10.1515/opar-2020-0123. S2CID 233015927.

- Hanks, B.; Linduff, K. (2009). "The Sintashta Genesis: The Roles of Climate Change, Warfare, and Long-Distance Trade". In Hanks, B.; Linduff, K. (eds.). Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals, and Mobility. Cambridge University Press. pp. 146–167. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511605376.005. ISBN 978-0-511-60537-6.

- Koryakova, L. (1998a). "Sintashta-Arkaim Culture". The Center for the Study of the Eurasian Nomads (CSEN). Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- Koryakova, L. (1998b). "An Overview of the Andronovo Culture: Late Bronze Age Indo-Iranians in Central Asia". The Center for the Study of the Eurasian Nomads (CSEN). Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- Kuzminykh, S. V.; et al. (December 2023). "Non-ferrous metal tool complex of the Petrovka Culture of Northern Kazakhstan: morphologi-cal and typological characteristics". Сетевое издание (in Russian). 63 (4). doi:10.20874/2071-0437-2023-63-4-4. ISSN 2071-0437.

- Kuznetsov, P. F. (2006). "The emergence of Bronze Age chariots in eastern Europe". Antiquity. 80 (309): 638–645. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00094096. S2CID 162580424. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012.

- Kuzmina, Elena E. (2007). Mallory, J. P. (ed.). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004160545.

- Lindner, Stephan (2020). "Chariots in the Eurasian Steppe: a Bayesian approach to the emergence of horse-drawn transport in the early second millennium BC". Antiquity. 94 (374): 361–380. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.37. ISSN 0003-598X.

- Lubotsky, Alexander (2023). "Indo-European and Indo-Iranian Wagon Terminology and the Date of the Indo-Iranian Split". In Willerslev, Eske; Kroonen, Guus; Kristiansen, Kristian (eds.). The Indo-European Puzzle Revisited: Integrating Archaeology, Genetics, and Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 257–262. ISBN 978-1-009-26175-3. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; et al. (6 September 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457). American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- Anthony, David; Vinogradov, Nikolai (1995), "Birth of the Chariot", Archaeology, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 36–41.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691135892. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Bryant, Edwin (2001), The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513777-4.

- Diakonoff, Igor M. (1995), "Two Recent Studies of Indo-Iranian Origins", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 115, no. 3, pp. 473–477, doi:10.2307/606224, JSTOR 606224.

- Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H. P.; Tremblay, X. (2005). Āryas, aryens et iraniens en Asie centrale. Paris: Collège de France. ISBN 2-86803-072-6.

- Jones-Bley, K.; Zdanovich, D. G. (eds.), Complex Societies of Central Eurasia from the 3rd to the 1st Millennium BC, 2 vols, JIES Monograph Series Nos. 45, 46, Washington D.C. (2002), ISBN 0-941694-83-6, ISBN 0-941694-86-0.

- Koryakova, L. (1998a). "Sintashta-Arkaim Culture". The Center for the Study of the Eurasian Nomads (CSEN). Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- Kuz'mina, E. E. (1994), Откуда пришли индоарии? (Whence came the Indo-Aryans), Moscow: Российская академия наук (Russian Academy of Sciences)

- Kuzmina, Elena E. (2007). Mallory, J. P. (ed.). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004160545.

- Mallory, J. P. (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500050521. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Mallory, J. P. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1884964985. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2008). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500283721.

- Mathieson, Iain (23 November 2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature. 528 (7583): 499–503. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..499M. doi:10.1038/nature16152. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274.

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; et al. (6 September 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. bioRxiv 10.1101/292581. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- Parpola, Asko (2015), The Roots of Hinduism. The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization, Oxford University Press

References

- ^ Bashir, Elena (2007). "Dardic". In Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (eds.). The Indo-Aryan languages. Routledge. p. 905. ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

'Dardic' is a geographic cover term for those Northwest Indo-Aryan languages which [...] developed new characteristics different from the IA languages of the Indo-Gangetic plain. Although the Dardic and Nuristani (previously 'Kafiri') languages were formerly grouped together, Morgenstierne (1965) has established that the Dardic languages are Indo-Aryan, and that the Nuristani languages constitute a separate subgroup of Indo-Iranian.

- ^ Mahulkar, D. D. (1990). Pre-Pāṇinian Linguistic Studies. Northern Book Centre. ISBN 978-81-85119-88-5.

- ^ Puglielli, Annarita; Frascarelli, Mara (2011). Linguistic Analysis: From Data to Theory. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-022250-0.

- ^ Gvozdanović, Jadranka (1999). Numeral Types and Changes Worldwide. Walter de Gruyter. p. 221. ISBN 978-3-11-016113-7.

The usage of 'Aryan languages' is not to be equated with Indo-Aryan languages, rather Indo-Iranic languages of which Indo-Aryan is a subgrouping.

- ^ Chatoev, Vladimir; Kʻosyan, Aram (1999). Nationalities of Armenia. YEGEA Publishing House. p. 61. ISBN 978-99930-808-0-0.

- ^ Asatrian, Garnik (1995). "DIMLĪ". Encyclopedia Iranica. VI. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Paul, Ludwig (1998). "The Pozition of Zazaki the West Iranian Languages" (PDF). Iran Chamber. Open Publishing. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Indo-Iranian". Ethnologue. 2023.

- ^ "Glottolog 4.7 – Indo-Iranian". Glottolog. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ "Hindi" L1: 322 million (2011 Indian census), including perhaps 150 million speakers of other languages that reported their language as "Hindi" on the census. L2: 274 million (2016, source unknown). Urdu L1: 67 million (2011 & 2017 censuses), L2: 102 million (1999 Pakistan, source unknown, and 2001 Indian census): Ethnologue 21. Hindi at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

. Urdu at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

. Urdu at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)  .

. - ^ Schmitt 1987: "The name Aryan is the self designation of the peoples of Ancient India and Ancient Iran who spoke Aryan languages, in contrast to the 'non-Aryan' peoples of those 'Aryan' countries." harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSchmitt1987 (help)

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 408.

- ^ a b Mallory & Mair 2008, p. 261.

- ^ Anthony 2007, pp. 408–411

- ^ Lubotsky 2023, p. 259, "There is growing consensus among both archaeologists and linguists that the Sintashta–Petrovka culture (2100–1900 BCE) in the Southern Trans-Urals was inhabited by the speakers of Proto-Indo-Iranian".

- ^ Mathieson 2015, Supplementary material: "Sintashta and Andronovo populations had an affinity to more western populations from central and northern Europe like the Corded Ware and associated cultures. [...] the Srubnaya/Sintashta/Andronovo group resembled Late Neolithic/Bronze Age populations from mainland Europe.".

- ^ Chintalapati, Patterson & Moorjani 2022, p. 13: "[T]he CWC expanded to the east to form the archaeological complexes of Sintashta, Srubnaya, Andronovo, and the BA cultures of Kazakhstan.".

- ^ Chechushkov, I.V.; Epimakhov, A.V. (2018). "Eurasian Steppe Chariots and Social Complexity During the Bronze Age". Journal of World Prehistory. 31 (4): 435–483. doi:10.1007/s10963-018-9124-0. S2CID 254743380.

- ^ Raulwing, Peter (2000). Horses, Chariots and Indo-Europeans – Foundations and Methods of Chariotry Research from the Viewpoint of Comparative Indo-European Linguistics. Archaeolingua Alapítvány, Budapest. ISBN 9789638046260.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 402, "Eight radiocarbon dates have been obtained from five Sintashta culture graves containing the impressions of spoked wheels, including three at Sintashta (SM cemetery, gr. 5, 19, 28), one at Krivoe Ozero (k. 9, gr. 1), and one at Kammeny Ambar 5 (k. 2, gr. 8). Three of these (3760 ± 120 BP, 3740 ± 50 BP, and 3700 ± 60 BP), with probability distributions that fall predominantly before 2000 BCE, suggest that the earliest chariots probably appeared in the steppes before 2000 BCE (table 15.1 [p. 376]).".

- ^ Holm, Hans J. J. G. (2019): The Earliest Wheel Finds, their Archeology and Indo-European Terminology in Time and Space, and Early Migrations around the Caucasus. Series Minor 43. Budapest: ARCHAEOLINGUA ALAPÍTVÁNY. ISBN 978-615-5766-30-5

- ^ Mallory 1997, pp. 20–21

- ^ Grigoriev, Stanislav, (2021). "Andronovo Problem: Studies of Cultural Genesis in the Eurasian Bronze Age", in Open Archaeology 2021 (7), p.3: "...By Andronovo cultures we may understand only Fyodorovka and Alakul cultures..."

- ^ Bjørn, Rasmus G. (January 2022). "Indo-European loanwords and exchange in Bronze Age Central and East Asia: Six new perspectives on prehistoric exchange in the Eastern Steppe Zone". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 4: e23. doi:10.1017/ehs.2022.16. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 10432883. PMID 37599704.

- ^ a b Parpola 2015, p. 76.

- ^ Bryant 2001, p. 206.

- ^ Francfort, in (Fussman et al. 2005, p. 268); Fussman, in (Fussman et al. 2005, p. 220); Francfort (1989), Fouilles de Shortugai.

- ^ Bryant 2001.

- ^ Bryant 2001, p. 216.

Notes

- ^ A fourth independent branch, Dardic, was previously posited, but recent scholarship in general places Dardic languages as archaic members of the Indo-Aryan branch.[1]

- ^ Sarianidi states that "direct archaeological data from Bactria and Margiana show without any shade of doubt that Andronovo tribes penetrated to a minimum extent into Bactria and Margianian oases".[30]

Further reading

- "Contact and change in the diversification of the Indo-Iranic languages" (PDF). Dr. Russell Gray, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution.

- Baly, Joseph (1897). Eur-Aryan roots: With their English derivatives and the corresponding words in the cognate languages compared and systematically arranged. Vol. 1. London: Keegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company.

- Chakrabarti, Byomkes (1994). A comparative study of Santali and Bengali. Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi & Co. ISBN 81-7074-128-9.

- Kümmel, Martin Joachim (2018). "The morphology of Indo-Iranian". In Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Vol. 3. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 1888–1924. doi:10.1515/9783110542431-032. S2CID 135347276.

- Kümmel, Martin Joachim (2020). "Substrata of Indo-Iranic and related questions". In Garnier, Romain (ed.). Loanwords and substrata: Proceedings of the colloquium held in Limoges (5th-7th June, 2018). Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 237–277. ISBN 978-3-85124-751-0.

- Kümmel, Martin Joachim (2022). "Indo-Iranian". In Olander, Thomas (ed.). The Indo-European Language Family: A Phylogenetic Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 246–268. doi:10.1017/9781108758666.014. ISBN 978-1-108-75866-6.

- Lubotsky, Alexander (2018). "The phonology of Proto-Indo-Iranian". In Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Vol. 3. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 1875–1888. doi:10.1515/9783110542431-031. hdl:1887/63480. S2CID 165490459.

- Pinault, Georges-Jean (2005). "Contacts religieux et culturels des Indo-Iraniens avec la civilisation de l'Oxus". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 149 (1): 213–257. doi:10.3406/crai.2005.22848.

- Pinault, Georges-Jean (2008). "La langue des Scythes et le nom des Arimaspes". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 152 (1): 105–138. doi:10.3406/crai.2008.92104.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas, ed. (2002). Indo-Iranian Languages and Peoples. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-726285-6.

External links

- Swadesh lists of Indo-Iranian basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- v

- t

- e

| Luwic | |

|---|---|

| Baltic | |

|---|---|

| Slavic |

- Tocharian A

- Kuchean